A Dirge for My Andalusian Muse

Ears of an equine Andalusian

nearly picked my downcast nose.

I'd contrived this quant illusion

searching for some pithy prose.

A silly, dilly-dallied notion,

dreamt incomplete, not fully whole,

a piecemeal thread, a vague solution

unreeled from a half-crocked spool.

Could a mulish lop-eared, jack breed,

summon forth a tortured page,

transform a scribe, depressed and hackneyed,

into a clear-eyed, lauded sage?

I'd never perched on such a creature

fleshing out a metaphor,

while wishing to create a feature,

of fictive verse, and a little more.

No words have bloomed to full fruition,

I'd scratched out naught but soulless chatter,

while set upon this conjured apparition,

this braying spirit, clad in matter.

No moocow pulled from Joyce processed

emerged full from dreamy space.

My donkey rose from deep recesses,

from dark subconscious place.

Not Rosinante's brave companion.

Nor Sancho Panza's faithful friend.

No dappled, stalwart, storied champion.

No equal could I apprehend.

Was I this grazing, grizzled burro?

A fading echo of my past?

Devoid of light, enmeshed in shadow,

become a jaded, pompous ass?

The barren surface now portends

that maybe no toll therein knells,

no labored words, nor lines pretend

to mark where idle spirit dwells.

And so, I stare without emotion.

A canvas short of colored clause.

And mourn the loss of my devotion

to any convoluted cause.

I lie bewildered 'tween hill and vale,

abandoned, in a field of white.

And lament the lack of any tale,

nor any hint of sacred write.

An ode to writer's block...

Alleycats

The brick-paved alley where the men met ended at a large field, once part of a Pennsylvania Railroad yard. Years earlier, when Lenape was a bustling town, the brick passenger terminal built in 1895 had hummed with activity. The railyard served a passenger line connecting Lenape to Pittsburgh, while PRR freight lines hauled coal, local goods, and plate glass from the Pittsburgh Plate Glass facility in Ford City to points west. Dredging barges were a common sight on the Allegheny River at Lenape, mining alluvial sand and gravel from the Pleistocene age, which also played a part in the local economy. By the early 1960’s the town seemed a tired shadow of its former self. The coal and minerals were gradually depleted and over time would bring joblessness and poverty to the region, like air hissing from a worn balloon.

The derelict freight yard now served as a baseball field, hosting Little-League practices and local softball games. In a corner of the field, wedged between the back of a car repair shop and a small grocery store, lay the horseshoe pit, its steel spikes glistening in the summer sun.

A loud, metallic clang echoed off the ramshackle brick buildings lining the alley. A pair of pigeons, dull gray with their iridescent neck feathers, strutted along the edge of the roof line unaffected, accustomed as they were to the familiar clamor. They cooed as they moved, their heads bobbing and weaving as if they were being tugged on a leash by an unseen hand.

Below, four men, Irv, Frank, Leo, and Heinie, paired off forty feet apart, peered at the steel stake, which minutely vibrated from the force of the landed horseshoe. Sand in the pit released a small cloud of dust into the air.

“Yeah, baby. That’s the Magic Man,” Irv shouted, gleefully clapping his hands together. “How’s that look, partner?”

“Nice shot, Irv. Clean ringer,” Frank replied. “What’s that make? Seventeen to fifteen.”

“Wait, I thought we had sixteen,” Heinie countered.

“In your dreams, Kraut. Your math ain’t much better than your game,” Irv sneered. “Seventeen to fifteen, our lead. Go ahead and throw.”

Irv sold appliances at Lenape’s main department store, McCann’s. Frank worked as a laborer at the sand and gravel facility built along the Allegheny River. Leo played drums for a small band which performed at weddings and social gatherings. Leo’s band, The River Rats, focused on ethnic music and could entertain partygoers with everything from polkas to the Jewish hora and Appalachian step dances. Heinie worked in construction, mostly roof installation. Each had their unique personal quirks and history.

Irv, tall and thin, often told people that he suffered from the effects of his mother’s use of Thalidomide during pregnancy. The truth was his disfigurements were congenital, their cause unknown. Thalidomide was introduced in 1953, now ten years later, it had developed into a major global scandal. He had only three fingers on his right hand and an unnatural curvature on his left. From birth, Irv figured out ways to adapt to his disability.

One skill he had managed to master was baseball. The deformity created a unique pitching style, which he had learned to turn to his advantage. His body corkscrewed into a bizarre delivery which seemed to mesmerize the batter like a snake charmer manipulating a cobra. Early in life Irv had learned to outmaneuver the taunts of schoolchildren with his quick wit and athleticism. It helped that with his tall, wiry frame, he was also naturally strong and aggressive. Rather than being bullied, Irv became a bully himself, with a combative, tough-talking persona other kids learned to respect. “All bluster and bull shit,” Heinie had once said.

Later, that same self-confidence translated into commercial success, enticing locals into laying out their hard-earned dollars for the latest in time-saving conveniences: washers, dryers, refrigerators, and TVs at McCann’s Department Store.

Irv pulled a Chesterfield King from its pack and placed it in his mouth. With his right hand, the three fingered hand, he expertly held up the matchbook flicked open the cover and without removing the match bent it from the comb and slid the tip against the striker strip in one smooth motion. The match tip flared, and Irv held it against the cigarette inhaling deeply. Then he blew out the flame and folded the cover back into the footer.

“One of these days, you’re gonna set your face on fire, lighting a match from the book like that,” Frank said. Frank admired Irv’s dexterity with his disfigured hand. The guy could do amazing things with it, despite the absence of two digits.

“You would know, Frankie baby. You would know.” Irv responded, tucking the matchbook into the pocket of his chinos.

“Not funny, Irv,” Leo growled.

Frank shrugged, accustomed to Irv’s sarcasm. The four men had history together, and not only from their horseshoe competitions. The fire had affected them all, in one way or another. Frank’s burn scars covered twenty percent of his body, mostly his hands, arms, and upper torso. Those on his face were less severe.

Frank, a thin man with large hands, was nearly as tall as Irv. His scarred face, haggard and blotchy, bore the marks of heavy drinking, with telltale veins around his nose and bags beneath his eyes, that pressed his eyeballs into slits. His grandfather had emigrated from Krosno, Poland, skilled as a glassmaker, to take work at the Pittsburgh Plate Glass factory in nearby Ford City. PPG, a company founded by industrialist John Ford, had recruited craftsmen familiar with glass from all over Europe and brought them to America. Their mixed ethnic presence in this small town led to a cross-cultural community. Churches of diverse denominations have now sprung up, along with bars and private clubs catering to its manifold immigrant participants. As the largest employer in the area, Frank had hoped to follow in the footsteps of his grandfather and father at PPG, both employed at the glass factory. But his drinking and the aftereffects of the fire had limited his options.

Growing up, Frank spoke Polish at home and learned only basic English after starting grade school at Lenape. Isolated from other kids due to the language barrier, he grew up as a shy and withdrawn kid, rarely mixing in with the other children. After dropping out of high school, he married another local Polish girl, Elzbieta. Through Elzbieta, he had gradually learned English beyond the rudimentary vocabulary of childhood. Their early dates were often quiet evenings spent sitting on a bench along the Allegheny River poring over English lessons in the school textbook.

Elzbieta worked at Taylor’s Hoagie Shop, where the four Taylor ladies made the locally famous sandwiches with chipped ham, Italian cold cuts, or tuna (especially on Fridays and Holy days.) The ladies, outfitted in their hair nets and cotton dresses, chatting amiably with their customers, were not known for speedy service. However, few complained about the wait for a Coke, bag of Wise potato chips, and a hoagie sandwich served on a soft freshly baked, yeast roll. Frank and Elzbieta’s daughter, Sofia, now ten, was a friend and classmate of Marissa. She was born ten months after Frank’s Army service in Korea ended. There, he had earned a Bronze Star, but memories from his service haunted him and contributed to occasional binges with alcohol.

The four men bantered easily, exchanging friendly gibes as they played. Each grew up in the small, western Pennsylvania borough of Lenape, a community dominated by farmers and coalmine workers forty-some-odd miles northeast of Pittsburgh.

“We were talking about names for our team, “Irv said. He had suggested “The Four Horseshoemen of the Apocalypse,” to the group who were neither miners nor farmers, but townies. None of them really understood what the “Four Horseshoemen of the Apocalypse” meant, not even Irv, but it sounded clever. The four men all thought Irv more cultured than the average Joe, but the fancy moniker was something he’d overheard at a horseshoe pitching match he’d attended in Pittsburgh some years earlier.

“I don’t know, Irv,” said Leo. If we’re gonna be competing as a team, we oughta know what our name means.”

“It ain’t my fault you never read a book,” grumbled Irv. “’The Four Horseshoemen of the Apocalypse’ will spook other teams. Makes us sound fearsome… heroic. What’s your idea?”

“How ‘bout The Cats?” offered Leo. “Or, even cooler, The Hepcats.”

“What are you, some kinda Beatnik?” Heinie asked. “Look at us… Hepcats? We ain’t ‘hep.’ Polecats, maybe. And we’re sure as hell not heroes.”

“Alleycats’d be more like it,” countered Frank.

The four men laughed. “Yeah, that’s us,” nodded Irv with a grin. “Alleycats.”

Heinie threw a horseshoe in a high arc, extending his arm gracefully to complete the follow-through. It sailed through the air, flipping slowly, but landed short.

“Verdammt,” Heinie muttered under his breath. Then, with his second throw Heinie managed a leaner.

Heinrich Gerhard, “Heinie” to friends, was a friendly, outgoing man, whose cheerful enthusiastic manner made him easily liked. Several years before on a cold, wet April morning, Heinie slid off his roof during a repair and fell, fracturing his skull. He recovered, but the surgical scar and hair loss around it gave him a sinister appearance. He usually wore a Pittsburgh Pirates baseball cap to hide the scar. Like Leo, who had served stateside with an Army band, during the Korean War, he saw no active duty. Heinie served with the U.S. Army in Berlin as a signal corpsman. His ability to communicate in both English and German helped him as he laid telephone lines and listening apparatus in the divided German capital during the buildup to the so-called “Cold War.” He had occasionally been called upon to assist in translating conversations at CIA listening posts; eavesdropping on Stasi or Soviet intelligence.

Heinie now worked construction, His fall from the roof and concerns about any injury aftereffects led to a layoff from West Penn Power Company. He was no longer climbing telephone poles in spiked climbing boots, but nailing down roof shingles, the cause of his earlier accident. Heinie was single, a confirmed bachelor.

Frank took his turn next, executing a rotating toss. Each man had his individual technique; every throw a ritual repeated over time. The approach to the foul line, the grip, release, and physical follow-through were reflexive, unstudied, like the spiritual practice of a shaman.

Frank’s toss struck Heinie’s leaner, knocked it off the stake and sent it rolling out of scoring distance. Irv did a little jig across the court. Leo bit his lower lip to stay calm as he tried to ignore Irv’s antics. Often, Leo would bless himself before he threw calling on supernatural intervention to guide his hand. Leo didn’t know if God was a horseshoe fan, but reciting a little prayer now and then couldn’t hurt.

Leo, a short, stocky man with a thin mustache and prematurely graying close-cropped hair was a quiet man. A devout Catholic and member of the Knights of Columbus, Leo constantly chastised Irv for his irreverent remarks and outbursts. Still, he secretly envied the man’s brashness and foul language. He never felt capable of that behavior himself. At confession with Father Fahey, the rector at St. Mary’s Catholic Church, Leo’s guilt from Irv’s outbursts sometimes led him to confess Irv’s off-color stories, as if those sins were his own. Leo respected all authority with unquestioned obedience. He was married, without children, to Loretta who taught fourth-grade classes at St. Mary’s grade school.

The game continued without much further conversation. On Irv’s final toss, his ringer and leaner gave their side the win.

They adjourned to a stack of railroad ties, that served as both backstop and an impromptu lounge. The smell of creosote hung in the air. Frank opened a Schaeffer, then tossed the can opener to Irv, who was holding an Iron City. The head from Frank’s beer oozed over the lip of the can. He switched the can from his left hand to his right, then licked the foam off his fingers.

“Don’t want to waste any of that Schaeffer’s,” Irv said with a smirk.

Heinie helped himself to one of Irv’s Iron City’s. Leo drank black coffee from a Thermos. He poured it into the cup cover and screwed the cap back on. “No beer for me. Got a gig tonight.”

The men fell silent as they took their break.

Leo stole a glance at Frank’s scarred hands. “It’ll be two years next week since the fire. Doesn’t seem that long.”

Heinie nodded. “I saw the Livengood woman in town last week, coming outta Merchant’s Bank. I don’t think she noticed me, though.”

“I light a votive candle at the church now and then,” Leo said.

“It’ll take more than a candle and a few prayers to help that woman,” Irv said. He took a swig of his beer, running his three-fingered hand through his hair.

Frank said nothing. He brushed the cold beer can against his forehead.

*****

Marissa Livengood woke from a dream. In the dream she waded in the surf at the ocean. Now she realized she had wet herself, but not in her bed, her parents’ bed.

“Oh no,” she said quietly to herself, “Not again.”

Her dad, Tom, was away on one of his sales trips, which was both good and bad. She missed her daddy, of course, but when he was away, she liked to sleep in her mom’s bed. It had become a ritual and both she and her mom enjoyed the time together. It embarrassed her that she still sometimes wet the bed; she was now almost ten.

Quietly she got up, being careful not to wake her mother. In the dark, she could feel that the wet spot in the bed wasn’t bad, mostly she had soiled her nightgown and underpants. She crept out of the bedroom to the bathroom where the space heater sat. Marissa took off her underpants and laid them atop a corner of the space heater. It was not in the direct path of the glowing electric coils, but her underpants should dry there in a few minutes.

I’ll go up to my room, so I don’t make any noise if mum wakes up. Then I can come back down in a few minutes, put on dry pants and get in bed with her. Maybe by morning, the bed will be dry too, she thought.

Back in a corner of the attic she rested her head against the wall and soon fell asleep.

The fire began in the early morning hours. The Livengood house was a two-story brick home with an attic converted into a small bedroom. Like the other houses on King Street, it had once been quite upscale with carved mahogany woodwork, wainscoting and crown molding.

Irv ran from the end of the block, gasping for breath, the first to reach the scene. His two pack a day cigarette habit hadn’t slowed him down, but did leave him coughing and wheezing. Leo followed a couple of minutes later.

“What’s going on, Irv?” Leo called.

“Fire on the upper floors, looks like,” Irv said, between gasps. The Livengood woman is over there.” Irv nodded toward the woman now frantically pacing and screaming for help. “Marissa,” she yelled. “Anyone see my little girl?”

Leo looked around. “Anyone called the fire department?” he shouted. A few people from the street gathered, some pulling bathrobes and housecoats about themselves to ward off the morning chill. No one answered. The growing gaggle of neighbors shuffled about nervously, mumbling to one another, like a brood of chickens, unsure of what to do.

Gene Claypool, the next-door neighbor shouted “I called the firehouse a few minutes ago. They should be on their way. I’ll call the police too.” He disappeared back into his house.

“What do we do, Irv? We can’t just stand here,” Leo cried.

Frank suddenly appeared. He pushed through the small crowd of people running up the porch steps to the front door. It was locked. Mrs. Livengood had apparently fled through the kitchen door in the back. Frank didn’t hesitate. He threw his shoulder into the door, which made a loud crack but remained closed. Frank charged the door again. This time it gave way with a loud crash, nearly tumbling him into the interior. From the street, Leo watched him grab the stair railing and charge up the stairs.

Outside, the crowd heard glass from the second-floor window shatter, smoke pouring out of the opening. The sound of a siren now filled the air signaling the approach of a fire truck.

“My God,” Mrs. Livengood screamed. “Marissa, Marissa!”

Inside the house, Frank rushed up to the second floor. The smoke had begun to descend from the stairway above leading to the attic. He called out, “Anyone here?” There was no response. He could hear flames crackling and smoke pouring from the bathroom off to his right. It hung along the ceiling on the second floor, some trailing up the stairway toward the attic. He looked quickly into the two bedrooms on the second floor but saw they were empty. He climbed the stairway to the attic, following the smoke. Frank could feel the heat rising as he ascended the stairs, acrid fumes stinging his eyes and the smoke obscuring the stairwell.

“Marissa, can you hear me? Where are you?” Frank shouted. “Marissa, Marissa...”’ Flames licked up the stairwell after Frank. It appeared that the fire had begun in the second-floor bathroom, and the fire was spreading quickly. Blisters formed on the stairway banister. Frank entered the small bedroom which had been created from the attic space. A small, battered dresser along the wall above the bathroom was beginning to smoke and it appeared to Frank that flames had were curling up the flocked wallpaper along the interior wall from below and now danced about the feet of the dresser.

The smoke was becoming thicker now and Frank crouched low, looking for the child. He was wearing jeans, slippers and a pajama top, which now felt as though it were clinging to his skin. Frank yanked the small bed away from the wall and saw the little girl curled in a fetal position on the floor next to the bed. As he clawed at the bed post to pull it away from the child, he could feel the intense heat emanating from the wall. He removed his pajama top and covered the girl for protection from the heat and smoke. Frank scooped up the girl into his arms, the smoke gagging him.

“Marissa, can you hear me?” He cried out at the girl, but she did not respond. She felt limp in his arms. Frank backed out of the room leaning his shoulder against the wall as he navigated carefully down the stairs. The smoke was thicker now, and he couldn’t use his hands to feel his way along the stairs with the child nestled in his arms. On the second floor, Frank could see flames roaring from the bathroom. He suddenly thought of his own bathroom which had a gas-fed space heater. Was there such an appliance here? He knew they were common in these old houses. Got to get out before the flames ignite that gas line.

A new wave of urgency hit Frank, He found the top stair leading down from the second floor with his foot and quickly, but carefully descended again, leaning his shoulder against the wall to avoid tripping down the stairs. He moved backwards down the stairs hunched over the bundle in his arms as if he were climbing down a ladder. By the middle of the stairway, leading from the second floor to the first, he could finally see beneath the smoke, which writhed about his head like a dark swirling veil. He could now hear sirens wailing outside. Above he could hear a soft whoosh as flames engulfed furnishings in the bedrooms. Finally, he reached the bottom of the stairs. The room was clear of smoke. Frank could feel fresh air entering the room from the open door as he staggered toward it. He was still crouched over the girl trying to shield her from the heat above them. He felt as if his flesh was on fire, but the only thought driving him was reaching the door to the outside.

Then he suddenly felt light-headed. His body swooned and his legs felt unsteady. He stood motionless at the bottom of the stairwell trying to clear his head, but he felt himself losing his thought processes. He couldn’t get his bearings and felt himself weaving in place. Can’t lose consciousness, he thought vaguely. The child in his arms felt heavy and he fought the urge to loosen his grasp on the small form.

Then he was aware of a hand on his arm. It pulled him gently forward as his right foot took a tentative step. He realized that a fireman was at his elbow guiding him toward the front door. The morning light outside poured through the open door illuminating the room. There he stood a moment, confused and shaking as the child was lifted from his arms. A second fireman reached around his waist and led him away the interior of the home out onto the front porch. Slowly they descended the porch steps onto the front lawn. With the fireman’s help, Frank staggered into the middle of the yard. Then he bent over and retched violently into the grass as fresh air entered his lungs, supplanting the soot and smoke. Firemen bustled about the yard, pulling on hoses connected to the hydrant in the street to the house. A second fire truck had arrived, extending a ladder to the open second-floor window.

Two men stepped forward, one at each arm, and guided him away from the frantic activity of the firemen.

Through the haze in his mind, Frank saw Heinie and Leo. Heinie had joined Irv and Leo while he was inside the house. They were talking to him, but he couldn’t understand what they were saying.

“Frank, can you breathe?” Leo said. “Are you all right?”

“I don’t think he can hear us, Leo,” Heinie said.

“I’ll grab one of the ambulance guys,” Irv said, who had now joined his friends. He had been keeping the crowd back from the house as help arrived.

Irv ran to one of the firemen, overseeing the crew as they doused the second-floor window with water. “Hey, can you help our friend? He can’t breathe and looks badly burned.”

The fireman held up his hand. “Yeah, we’ll be with you in a minute, fella. We’re trying to resuscitate the kid and get this fire under control.”

Irv looked over to where two firemen were kneeling in the yard trying to breathe life into Marissa. Her inert body was not responding. Several people were standing around watching. The pair administered CPR, a technique recently introduced to local fire crews, alternating between mouth-to-mouth breathing and chest compressions.

Mrs. Livengood stood by helplessly as the fireman attended to her daughter, her hands covering her mouth as tears streamed down her face. A neighbor woman had her arm around her. Behind them more fire trucks were arriving. A ladder had been extended to the second floor and a fireman was climbing it, guiding a fire hose into the second-floor window which had smoke and flame coming from its shattered panes.

Minutes later an ambulance attendant wheeled a stretcher over to Frank. He was fidgeting, trying to speak, when one of the ambulance attendants came to him lying in the yard. “Help me lift him onto the stretcher,” the fireman said to Heinie, who had shaken off his jacket. He was hatless. A thin wisp of hair was twirling in the morning breeze. Heinie gently held Frank’s legs and the fireman gingerly lifted Frank from under his armpits. Frank’s body was convulsing in spasms, coughing, and moaning in pain. The shock and adrenalin rush from the rescue was now easing and the physical injuries he’d sustained were taking over. Panic swept across his face, causing his eyes to dart nervously from one man to the other.

“We need to get you to the hospital to attend to these burns,” the attendant said. “Please people, move back now, so we can get this man’s stretcher into the ambulance.”

Frank looked up at the man. “I’m fine for now. Help the girl first. She needs you more than I do.”

“Might have been true earlier,” the attendant responded grimly. “But she’s gone.”

“Gone,” Frank asked. “Gone where?”

“She’s dead.”

Stunned, Frank lay on the stretcher waiting for the ambulance crew, and watched the firemen fight the fire. He saw Mrs. Livengood approach him; her fists clenched. Tears had formed streaks down her face, where they had washed away the smoke and soot.

“Why couldn’t you save her?” she shrieked. “Why return a dead child to me?”

Then she wandered back to the house, sobbing uncontrollably, pushing away anyone who tried to comfort her.

Frank spent one day and night at Lenape Hospital, a small 40-bed facility. Elzbieta stayed by his side while their daughter, Sofia, stayed with Elzbieta’s parents.

The next day, an ambulance transported him to Mercy Hospital in Pittsburgh for isolation and burn treatment. Founded by the Sisters of Mercy in 1847, the Catholic hospital was better equipped to deal with his recovery than the small hospital in Lenape. As a teaching hospital, Mercy would later establish the first dedicated burns unit in the country in 1967.

The investigation revealed the fire started in the bathroom’s electric space heater. It had been contained to the upper floor. Apparently, the child had wet her bed and laid her wet underpants and nightgown by the glowing coils to dry, hoping her mother wouldn’t find out. The clothing caught fire, sending flames traveling up the wallpaper along the ceiling, with smoke and gases following into the attic above. The child had been asphyxiated before the flames reached her bed. She was dead when Frank carried her out of the house into the yard.

Frank spent a month in Pittsburgh before returning to Lenape. Eventually every member of the horseshoe team made the drive to Pittsburgh. The winding two-lane Route 28 from Lenape to Pittsburgh was a grueling journey. Drivers had to slow down through each small town…Natrona Heights, Tarentum, New Kensington … following the winding Allegheny River in the years before heavy automobile traffic. The journey was made more treacherous by lumbering coal trucks, grinding gears as they struggled up the steep inclines of the Allegheny Mountain range, then barreling down the other side, brakes screeching. A driver simply had to grit his teeth and bear it.

*****

Irv was the first of his friends to make the journey to Pittsburgh

“Hey partner, how you doin’?” Irv said, setting down a small bouquet of flowers on the bedside table. “Don’t go thinkin’ I’m askin’ ya to go steady or nuthin.’. I just grabbed these flowers along the road as I came down 28.”

“That’s good, Irv. My wife and kid’ll be happy to know I ain’t cheatin’ on ‘em.”

“The Sisters takin’ good care of ya? This place makes our little hospital look like somethin’ made outta Lincoln logs.”

“All the modern conveniences,” Frank replied with a grunt. “You come here all by yourself? Ambulance that brung me took more’n an hour.”

“Damn coal trucks. Scare the hell outta me,” Irv responded. “And ya can’t just pull over. Ain’t no shoulders along half the road.”

“Sorry, man. Appreciate you comin’ to visit. How’re yinz doin’ back home anyway?”

“Not bad. The local Horseshoe Pitchers Association says they prefer horseshoe teams as two guys, for doubles play, but they’re okay with four-man teams. You and I are the main two members of Alleycats, but Leo and Heinie fill in when they can. Leo’s got to play a lot of band dates during matches and Heinie… well, he ain’t that good. I need you back in the lineup.”

“Doctor says I’ll be able to pitch, eventually. May not be much to look at, swimmin’ up at Crooked Creek beach, but…” Frank’s voice trailed off.

“You can take me with you when you take the family swimming. The ladies’ll be too busy checkin’ me out to notice you.”

“Those two hot dogs still rollin’ on the hot plate in the window at Al’s Tavern?’ Frank asked, smiling.

“Hell, those two hot dogs been travelin’ on them rollers since the fifties,” Irv replied.

They both laughed. Irv and Frank talked town gossip, so Frank could keep with all the “Lenape news.”

A week later Leo and Heinie came together for a visit. Leo brought a library book about the Big Band Era and Heinie brought some magazines, Argosy, Field and Stream, and some Reader’s Digest back copies.

“The magazines were mine. I was offered some magazines from Sully’s Barber Shop, but they was too worn out to read. Sully said to get well and hurry back,” said Heinie.

“I imagine the National Geographic’s South Seas Island Natives’ issue was pretty-well thumbed,” Frank said with a grin. Sully kept it in the back.

“Yeah, Irv showed up at Sully’s twice the same week when that issue came out,” joked Leo.

“I heard Sully sent him home the second time he came in. Said Irv didn’t have enough hair to cut,” Heinie added. The three men laughed.

“Saved him from committing a venial sin,” added Leo, making a hand gesture.

A brief silence ensued as the laughter subsided.

“You were a hero, Frank, charging into that burning house,” Heinie said.

“It ain’t heroic, saving a dead child,” Frank replied bitterly.

“Wasn’t your fault, Frank,” said Leo. “You didn’t know the girl was dead.”

“You didn’t start the fire either,” Heinie said. “None of us ran into that burning house, only you.”

“Yinz helped the firemen, outside,” said Frank. “I saw that.”

“Sure, we did,” Heinie responded. “Not the same thing.”

“No one knows how they’ll react in that kind of situation,” said Leo, thoughtfully. “I remember when the Korean War started, and we all signed on…”

“Except, Irv, of course,” Frank said.

“Of course,” Leo continued. “I thought I could go and fight. Lot of boys went. But you were the only one who saw action. They sent Heinie to Berlin and you to Korea. I chickened out. I saw a notice that the Army was putting a band together to play USO tours and signed up. Never left stateside. I’ve always wondered if I had what it takes, you know, if I had the balls to handle combat. It haunts me y’know?”

“Hell, Leo,” said Frank. “It don’t take balls. You do what you’re told. I fought in that first Pork Chop Hill Battle in April. Soiled some perfectly good G.I. drawers. But we took the hill. So what? Some good boys died takin’ it, a lot of ‘em. Then we left and the damn Chinese came back and took it in July. Just stupid. That’s what war is, stupid. Bunch of damn Generals movin’ pieces on a game board.”

“Still, I wonder, could I do it? I think about it now and then,” Leo said shaking his head. “You, a hero and all. A Bronze Star, that’s something, and now this fire thing.”

“C’mon Leo. Jesus, no regrets,” Frank said. “That’s just crazy thinking. Bangin’ on them drums. That’s what you did. Helpin’ cheer guys up who’s away from home. You did your part. Besides, just so you know. It was a Silver Star I got. Elzbieta was so proud she had it bronzed.” Frank grinned and leaned back on his pillows.

“I did my part, too,” said Heinie, “Drinkin’ a lot of good German lager.”

“And still drinkin’ a lot of good German lager,” Leo said. “Ok, maybe not good German lager, but a lot of Iron City.”

“Ain’t that the truth?” added Frank.

The three friends chatted amiably for a while exchanging stories and happenings back home. Talk about their regrets and things they could or should have done in life, forgotten.

Soon Frank was well enough to return home, no longer fearing infection in his burns. Elzbieta changed his bandages carefully, applying the prescribed salve to speed his healing. Sofia wrinkled her nose when she visited his room.

When she came out of the room, she tugged at her mother’s dress.

“I don’t like the way that medicine smells on Daddy,” she complained.

“Shh, Sofia, Daddy needs this medicine to get better. He probably doesn’t like the smell either, so let’s not mention it. We wouldn’t want to hurt his feelings.”

“Okay, Mommy, I won’t.”

“Good. Now go outside and play.”

Elzbieta knew the smell wasn’t from the salve; it was the burnt flesh of his wounds. Frank, however, could no longer smell them as they slowly healed.

As he recovered, his days were spent sitting in a weathered Boston Rocker on the front porch, drinking beer and watching the quiet bustle of the street. Often his friends would come by trying to cheer him up from his bouts of guilt and depression. While others saw bravery in his attempt to rescue the child from the burning house, Frank saw only his failure to save her. On those rare occasions Frank saw Marissa’s mother in the street, they avoided each other. Frank would drop his head, feigning sleep as Mrs. Livengood turned her gaze away from the silent man sitting on his porch.

*****

One day, several months after he returned home, Mrs. Livengood stopped at the porch to speak with Frank. It was the first time they had spoken.

“Mrs. Livengood,” Frank nodded to her. “Good afternoon.”

“Cherie, please.”

Frank motioned her to come up on the porch.

“Ok then, Cherie. I’ve been meaning to come by and…”

“I know,” she said, her voice soft. “Me too. It’s… awkward.”

“I don’t know how to say how sorry I am… about little Marissa.”

“It’s me who should apologize. I spoke cruelly to you that day, and I know I can’t take it back. Mr. Solaski…” She hesitated, her voice faltering. “I have been meaning to thank you.”

“It’s Frank. Please call me Frank.”:

She closed her eyes searching for the right words. “You risked your life trying to save my little Marissa…”

Frank couldn’t look her in the face. His head bowed. “There’s no need…”

“Only, every time I see you, it reminds me.” She stopped, not knowing what she wanted to say. They were silent; two forlorn figures in the street, a gulf of despair between them, which neither knew how to navigate.

“I’m sorry,” Frank said, his voice trailing off, never raising his head.

“The firemen investigating the cause of the fire said they think it began in the bathroom,” Cherie began. “Some burnt bits of clothing were found by a space heater we used in the bathroom. My guess is that Marissa wet the bed; she did that sometimes, especially when my husband was away. She would dry her nightclothes with the heater, to pretend the accident never happened. She never thought I knew.”

“Cherie, you don’t have to explain any of this to me.”

“I wanted you to understand. I woke up to the smell of smoke. Marissa was sleeping in my bed, but when I reached for her, she wasn’t there. I called out her name, but she didn’t answer, so I assumed she had also smelled the smoke and ran outside to get help.”

“Maybe she tried to wake you. Was the smoke thick?” Frank asked.

“No, not really. I didn’t know where the smoke was coming from. I ran downstairs and out the back door, through the kitchen. I kept calling her name, but she didn’t answer. I figured she had run to get a neighbor, maybe. I just panicked. The back door locked behind me. The firemen had to break in the back door to get through. I kept calling her name outside, but she wasn’t there either. I didn’t know where she was. I ran around the yard yelling her name. I was hysterical. Then I saw you bust open the front door and run upstairs. That was the first time I realized she was still in the house.”

“I remember. I was thinking of my daughter, Sofia. What would I do if she were in a house on fire? I just acted out of instinct.”

“Then afterwards you were in the hospital. I remember your wife at Marissa’s funeral. She sent me the most beautiful card.”

“When I came home, Elzbieta said we should come by to pay our respects…but I thought…” Frank paused. “I don’t know what I thought.”

“You thought I blamed you for Marissa’s death because of what I said. I was wrong, but I didn’t know how to approach you. I was so cruel that day. I’m ashamed of what I said to you.”

“You were terrified, upset. I came to realize that. They were just words.”

“Words can wound people. They can leave scars…more than the fire itself. And for all that, I am very sorry. Can you ever forgive me?”

“We all have scars, Cherie.” Frank rubbed his forehead, struggling for the right words. “People are from a place, of a place. We’re like these mountains around here. Coal companies come in, scrape the land flat, dynamite it to get to the coal, or drill holes in the earth. They leave the place in ruins then move on to the next site. Destroy the landscape to get what’s beneath. People are pretty much the same. Mistakes, choices…life leaves its mark. Scars on the outside, scars on the inside. Some you can see, some you can’t.”

“That’s true,” she said. “We all have our scars, then just try to move on.”

“I hold no grudge, Cherie, nothing to forgive. I just wish I could’ve saved your baby.”

Cherie nodded. There were tears in her eyes. She suddenly broke into a smile.

“Oh. I wanted you to know, also...” She dried her eyes with her sleeve. “We’re expecting another child; I’m three months along. Not a replacement for Marissa, just a new start.”

“No kidding. That’s great,” Frank said with a smile.

“Tom and I have decided that if it’s a boy, we’re going to call him Frank. If that’s okay?”

Now it was Frank’s turn to tear up.

“Aw, there ain’t no need to do that,” he said. “What if it’s a girl?”

“Francine. That was my grandmother’s name too. So, you can share that honor with her.”

“I don’t know what to say, other than I am honored. Thank you.”

“You and your friends tried so hard to help that day. You in the house, the man with the bad hand managing the onlookers, while your other friends were helping the firemen. It took me a long time to see that. All your horseshoe friends, trying to help. I hear the clank of those horseshoes all the way up at my house. To me you’re all heroes.”

Frank smiled and shook his head. “Heroes? We’re no heroes, Cherie. We’re just a bunch of guys in the neighborhood. Alley cats, that’s all we are.

She looked up and nodded. “I’m glad we finally talked. Sorry it took so long.”

After a moment of silence, she stepped down from the porch and walked carefully towards home, her heels clicking on the brick-paved sidewalk.

*****

“Yinz up for another game?” Irv asked. He brushed away dirt on his chinos from the railroad ties and drained the last of his beer.

“Maybe, if I got time before for my gig tonight,” Leo said.

“Sure,” Frank and Heinie said in unison.

“Y’know, Frank, you never told us how Mrs. Livengood apologized for blaming you at the fire,” Leo said.

“It’s kinda personal,” Frank mumbled. “Not important.”

“Well, she shoulda been more grateful when you ran into her burning house,” Irv said. “But I get it, I mean she wasn’t in her right mind and all…”

“Yeah, it was a pretty piss-poor way to say, ‘Thanks for trying.”” Heinie added.

“We talked. It’s cool,” Frank said. “My wife spoke with her too. Sometimes people say things they don’t mean. Heat of the moment kinda thing.”

“Plenty of heat in that moment,” Irv said, pausing. “Guess she’s had another kid. Saw her pushing a stroller down Water Street.”

“Francine,” Frank said. “Named for after grandmother. Hope it helps ‘em.”

“You should’ve seen the girl’s funeral,” Leo said. “While you were at Mercy, there must’ve been a couple hundred people there. I went with Loretta. They’re Lutherans. St. John’s was full, and people stood outside on the steps, showing their support. That little casket… broke your heart.”

“In a town like this, people come out,” Heinie said. “They took up a collection, mostly from all the churches. Paid for the funeral and then some.”

“Elzbieta told me at the hospital. She said all people wanted to talk about at the hoagie shop was the fire and the funeral,” Frank said.

“I talked with Father Fahey about it,” Leo said. “Asked him why these things happen, God bein’ merciful and all…”

“Let me guess,” Irv said, pulling another beer from the cooler. “God works in mysterious ways. Bunch of crap. Things happen because they happen. Ain’t no God behind it, no plans. We’re all on our own.”

“Fate. Chance, whatever you call it,” Heinie said. “I ain’t a religious guy, like Leo, but something’s gotta make the world work. Maybe that fire had to happen. Maybe Frank had to go into that house, ya know? I’m not sayin’ it’s God, but….”

“Bah. You think some unseen hand is jerkin’ our strings?” Irv responded. “I don’t buy it. We ain’t puppets. There’s a reason for everything. Somethin’ happens halfway around the world and that causes something else to happen here. Cause and effect. It’s just we don’t always see the cause. That’s my theory, anyway.”

“Maybe,” Frank said. “Maybe it’s a little bit of all that. Who knows? It’s not like we’re gonna figure it out sittin’ here. Hey, weren’t we gonna throw some horseshoes?”

“I better pass,” Leo said, checking his watch. “Cutting it too close to make our event tonight. BPOE, the Elks Club.”

“BPOE. What’s that stand for, anyway,” asked Heinie.

“Beer Pours Out Easy, I heard,” Irv said with a grin.

“I don’t know,” Leo said. “Something with Elks in it. Just another social club.”

“’Beer pours out easy’ sounds like a club this sorry group could get behind,” Frank said. “C’mon let’s play another round.”

Soon, the loud metallic clang of horseshoes echoed off the run-down buildings in the alley behind King Street, and all was right in the world.

Copyright © 2025 Jack O’Brien

Author Portfolio

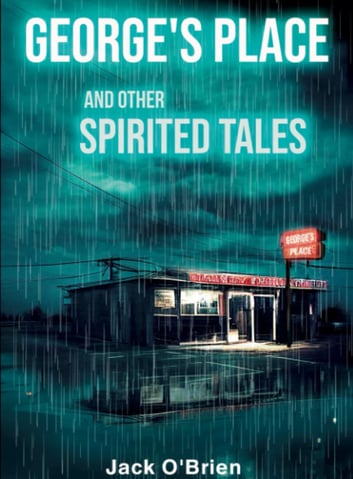

George's Place and Other Spirited Tales

Georges Place and Other Spirited Tales is my debut collection of short stories born from the depths of my imagination. Over the past eight or nine years, I have compiled, revised, written, and rewritten these stories.

This collection takes you on a journey through diverse settings, from Western Pennsylvania to Texas, Illinois to Ireland, and New England to the Old West. Each tale presents characters and circumstances as distinct as can be imagined. Within these pages, you will find mystery and memoir, humor and politics, philosophy, and the profound emotions we experience in everyday life. George's Place and Other Spirited Tales offers a little taste of everything.

The book weaves together short anecdotes, a flash fiction, and short stories with the observations and musings of two wandering travelers. You'll meet a motley crew of Texas barflies and responding to a call for action, a young boy on the cusp of adolescence, seeking connection with his late father, by manipulating images in a mirror, an aging illusionist facing the reality of "real magic" for the first time, and a blind woman finding solace solely in the visual content of her dreams as she yearns for rebirth. Moreover, mystical characters from Irish fables spring to life to interact with the real world.

These captivating tales compete for your attention, aiming to entertain and delight. So, pull up a chair and let your imagination soar as these whimsical stories transport you through a range of human emotions, from laughter to tears.

book available for purchase on amazon

contact me: jack@jackslore.com

© 2024. All rights reserved.